https://dojang.io/mod/page/view.php?id=2366

33.3 클로저 사용하기

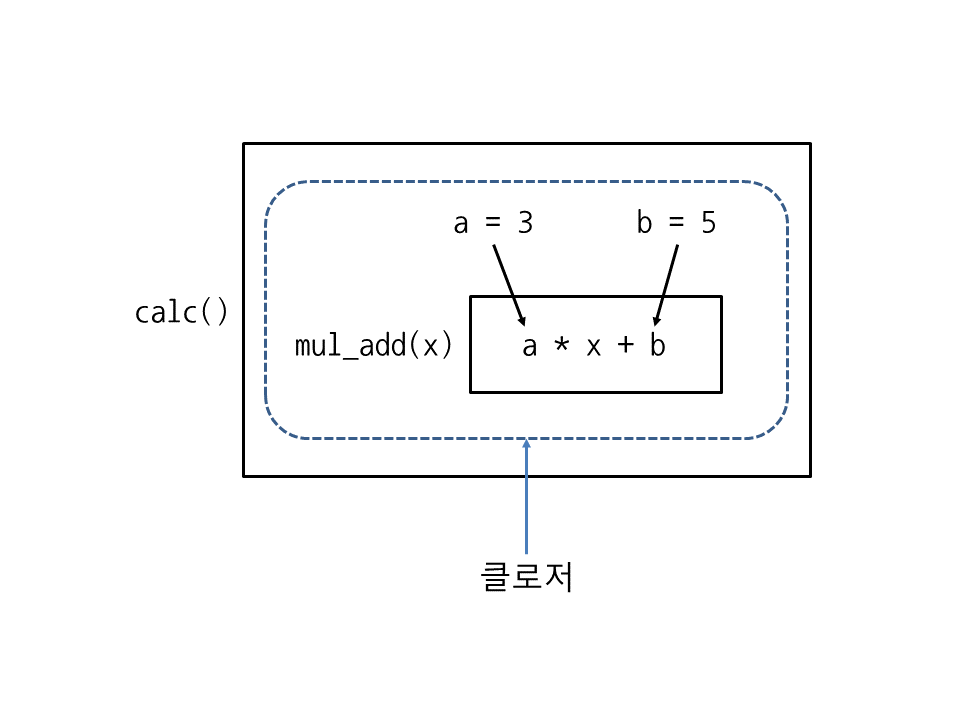

이제 함수를 클로저 형태로 만드는 방법을 알아보겠습니다. 다음은 함수 바깥쪽에 있는 지역 변수 a, b를 사용하여 a * x + b를 계산하는 함수 mul_add를 만든 뒤에 함수 mul_add 자체를 반환합니다.

closure.py

def calc(): a = 3 b = 5 def mul_add(x): return a * x + b # 함수 바깥쪽에 있는 지역 변수 a, b를 사용하여 계산 return mul_add # mul_add 함수를 반환 c = calc() print(c(1), c(2), c(3), c(4), c(5))

실행 결과

8 11 14 17 20

먼저 calc에 지역 변수 a와 b를 만들고 3과 5를 저장했습니다. 그다음에 함수 mul_add에서 a와 b를 사용하여 a * x + b를 계산한 뒤 반환합니다.

def calc(): a = 3 b = 5 def mul_add(x): return a * x + b # 함수 바깥쪽에 있는 지역 변수 a, b를 사용하여 계산

함수 mul_add를 만든 뒤에는 이 함수를 바로 호출하지 않고 return으로 함수 자체를 반환합니다(함수를 반환할 때는 함수 이름만 반환해야 하며 ( )(괄호)를 붙이면 안 됩니다).

return mul_add # mul_add 함수를 반환

이제 클로저를 사용해보겠습니다. 다음과 같이 함수 calc를 호출한 뒤 반환값을 c에 저장합니다. calc에서 mul_add를 반환했으므로 c에는 함수 mul_add가 들어갑니다. 그리고 c에 숫자를 넣어서 호출해보면 a * x + b 계산식에 따라 값이 출력됩니다.

c = calc() print(c(1), c(2), c(3), c(4), c(5)) # 8 11 14 17 20

잘 보면 함수 calc가 끝났는데도 c는 calc의 지역 변수 a, b를 사용해서 계산을 하고 있습니다. 이렇게 함수를 둘러싼 환경(지역 변수, 코드 등)을 계속 유지하다가, 함수를 호출할 때 다시 꺼내서 사용하는 함수를 클로저(closure)라고 합니다. 여기서는 c에 저장된 함수가 클로저입니다.

이처럼 클로저를 사용하면 프로그램의 흐름을 변수에 저장할 수 있습니다. 즉, 클로저는 지역 변수와 코드를 묶어서 사용하고 싶을 때 활용합니다. 또한, 클로저에 속한 지역 변수는 바깥에서 직접 접근할 수 없으므로 데이터를 숨기고 싶을 때 활용합니다.

33.3.1 lambda로 클로저 만들기

클로저는 다음과 같이 lambda로도 만들 수 있습니다.

closure_lambda.py

def calc(): a = 3 b = 5 return lambda x: a * x + b # 람다 표현식을 반환 c = calc() print(c(1), c(2), c(3), c(4), c(5))

실행 결과

8 11 14 17 20

return lambda x: a * x + b처럼 람다 표현식을 만든 뒤 람다 표현식 자체를 반환했습니다. 이렇게 람다를 사용하면 클로저를 좀 더 간단하게 만들 수 있습니다.

보통 클로저는 람다 표현식과 함께 사용하는 경우가 많아 둘을 혼동하기 쉽습니다. 람다는 이름이 없는 익명 함수를 뜻하고, 클로저는 함수를 둘러싼 환경을 유지했다가 나중에 다시 사용하는 함수를 뜻합니다.

33.3.2 클로저의 지역 변수 변경하기

지금까지 클로저의 지역 변수를 가져오기만 했는데, 클로저의 지역 변수를 변경하고 싶다면 nonlocal을 사용하면 됩니다. 다음은 a * x + b의 결과를 함수 calc의 지역 변수 total에 누적합니다.

closure_nonlocal.py

def calc(): a = 3 b = 5 total = 0 def mul_add(x): nonlocal total total = total + a * x + b print(total) return mul_add c = calc() c(1) c(2) c(3)

실행 결과

8 19 33

지금까지 전역 변수, 지역 변수, 변수의 범위, 클로저에 대해 알아보았습니다. 클로저는 다소 어려운 개념이므로 지금 당장 완벽하게 이해하지 않아도 상관없습니다. 나중에 파이썬에 익숙해지면 자연스럽게 익히게 됩니다.

'C Lang > Python Basic' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 제너레이터 사용하기2 - 제너레이터 만들기 (0) | 2019.11.06 |

|---|---|

| 제너레이터 사용하기1 - 제너레이터와 yield 알아보기 (0) | 2019.11.06 |

| 클로저 사용하기2 - 함수 안에서 함수 만들기: nonlocal 키워드 (0) | 2019.11.06 |

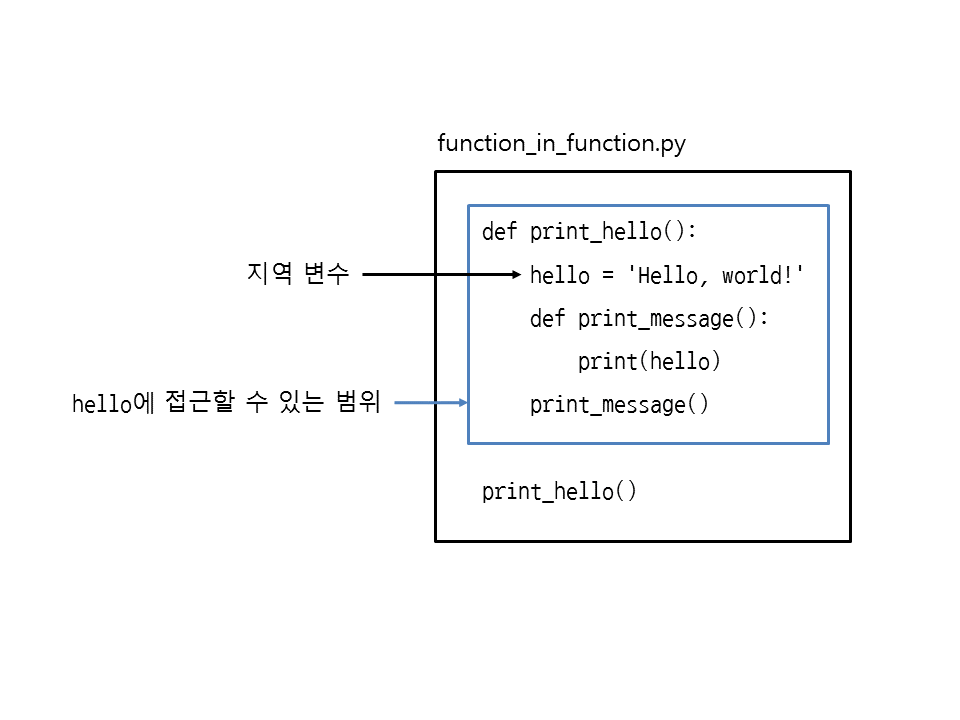

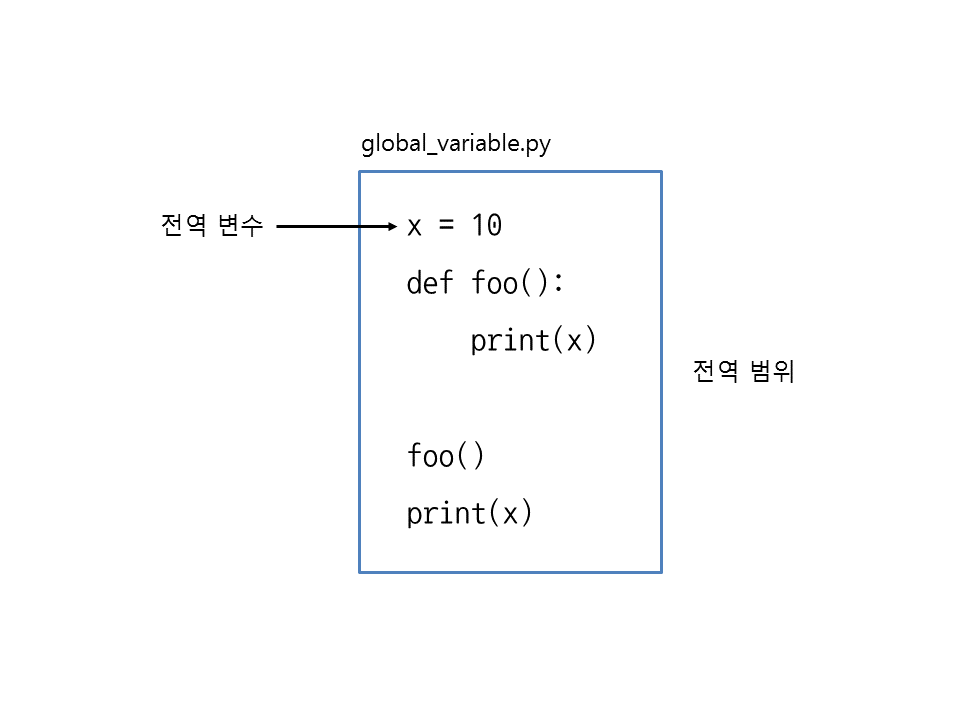

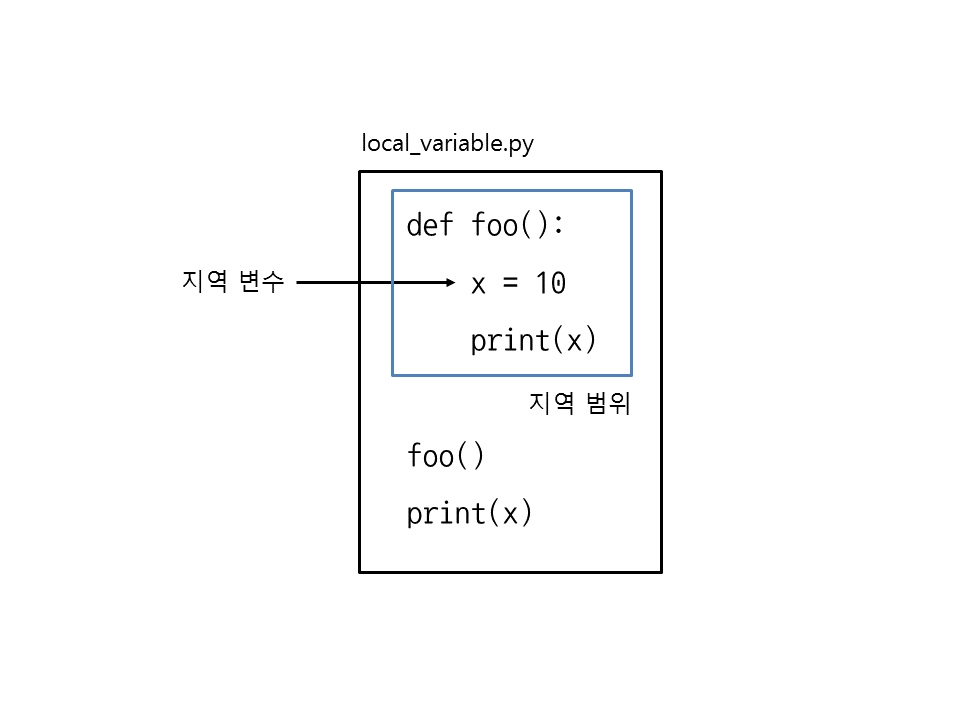

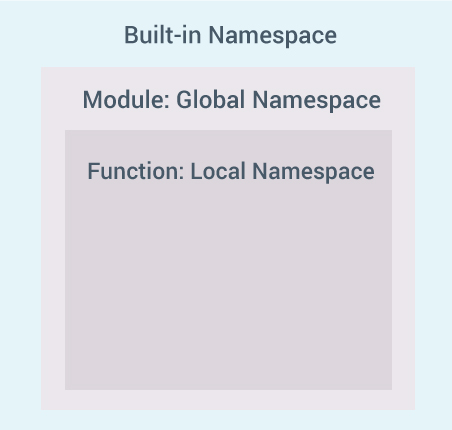

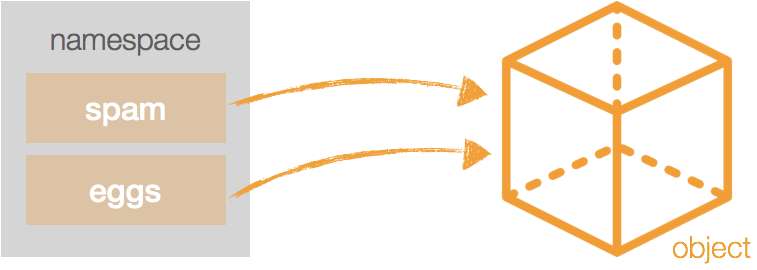

| 클로저 사용하기1 - 변수의 사용 범위 알아보기: 전역범위, 지역범위, 네임스페이스, global 키워드 (0) | 2019.11.06 |

| mutable과 immutable 객체, shallow copy, deep copy (0) | 2019.11.01 |