Expectations for the long-term trajectory of interest rates lie at the heart of a debate over the so-called neutral rate, or the interest rate at which the economy is in equilibrium, with monetary policy neither too tight nor too loose. A growing chorus of economists argues that structural shifts in the economy that were either introduced during or exacerbated by the Covid pandemic are pushing the neutral rate higher than it has been in decades.

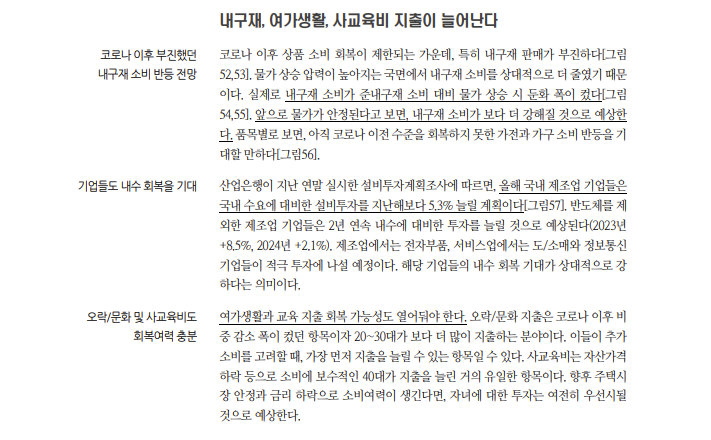

Advertisement - Scroll to Continue

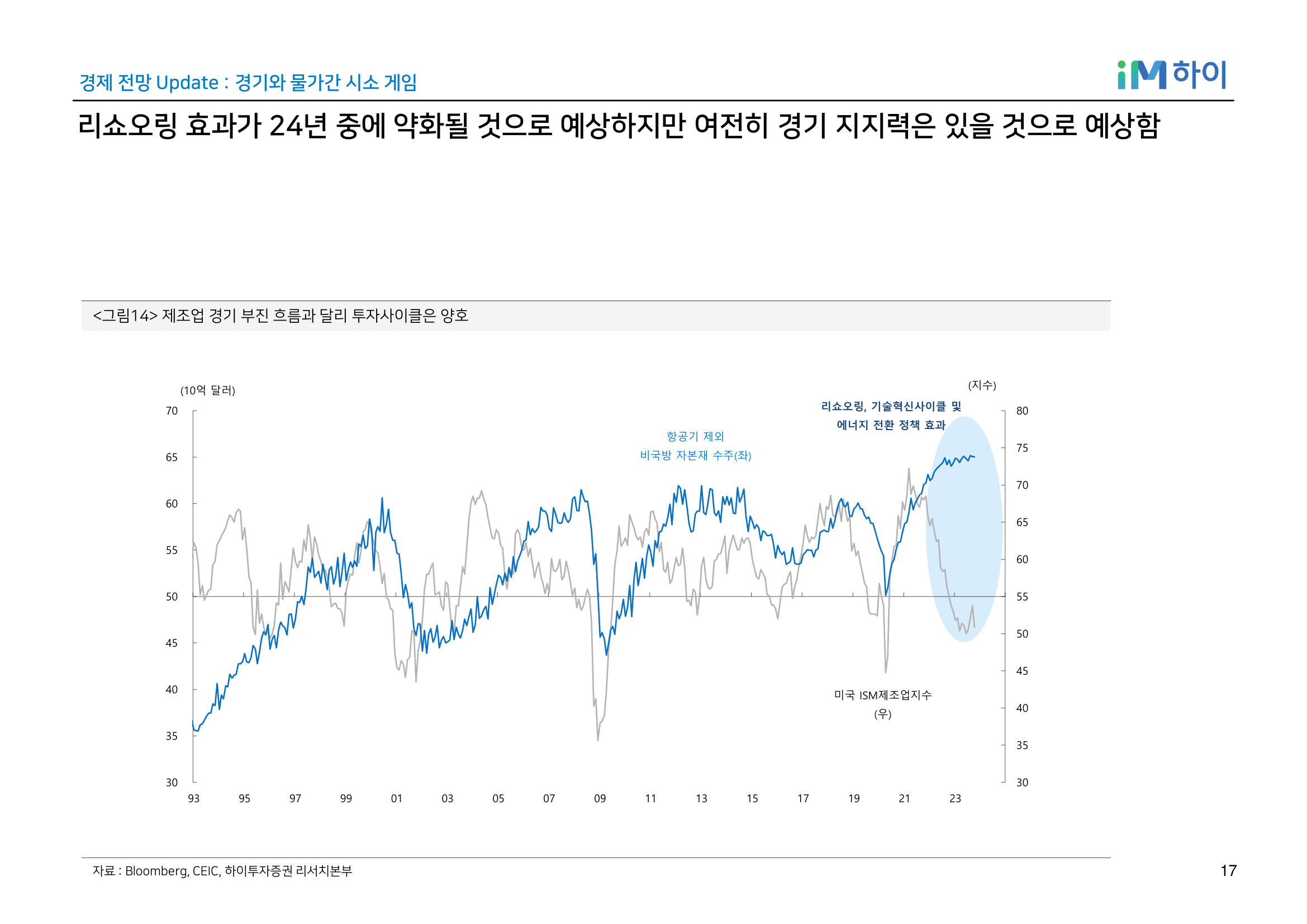

There are a handful of factors at play: Governments are spending more freely without raising taxes, pushing up deficits. Consumer demand has proved to be remarkably persistent. A slowdown in globalization has led to both a decline in trade volumes and a costly effort to bring supply chains closer to home, making consumer goods more expensive.

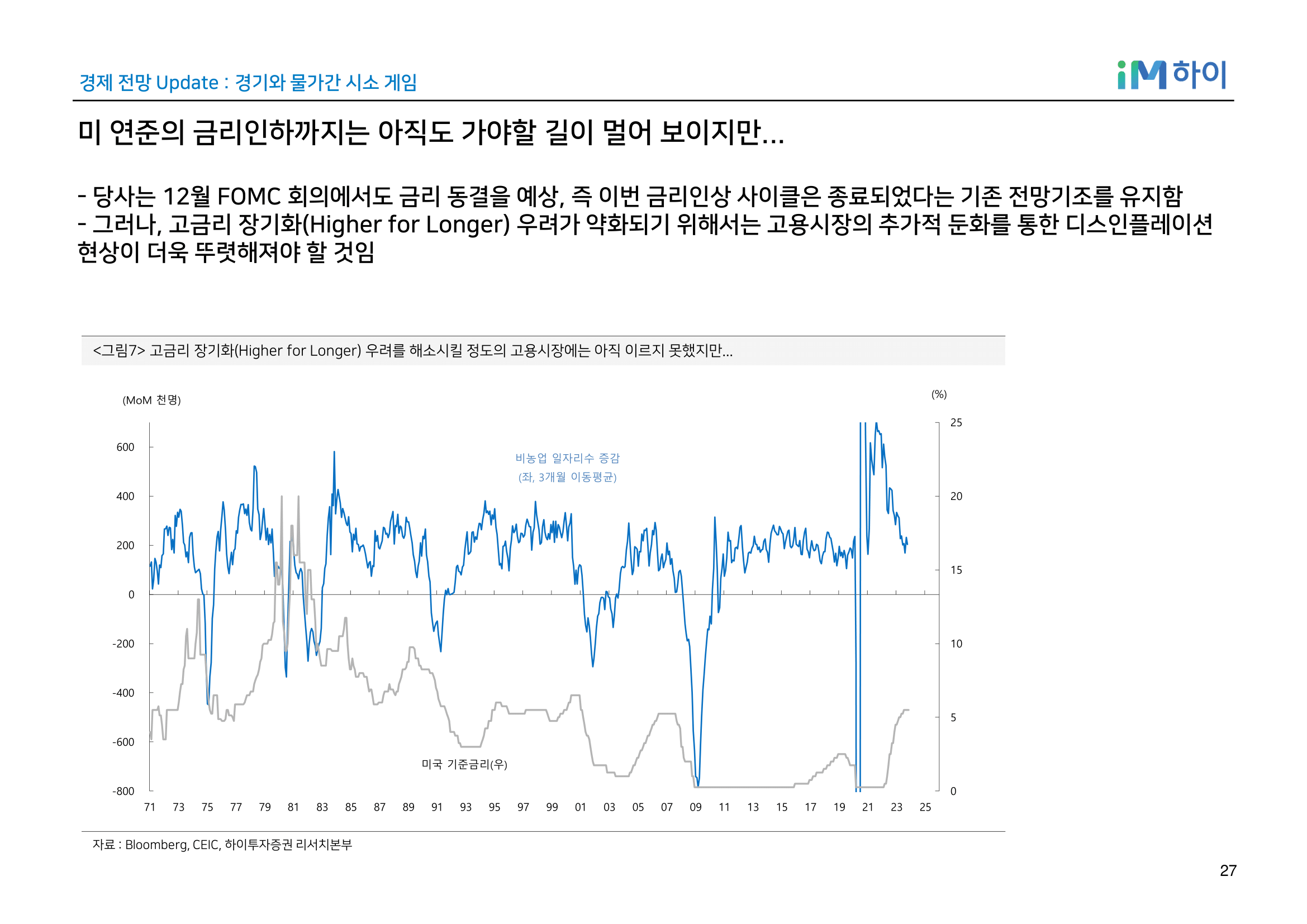

These changes, among others, have led to increased friction in the economy and will make it more prone to bouts of inflation moving forward, economists say, forcing monetary policy to run tighter as a result. Since 2019, Fed officials’ median forecast has put the longer-run federal-funds rate—effectively their estimate of neutral—at 2.5%. That equates to a 0.5% real neutral rate, after subtracting the Fed’s 2% inflation target.

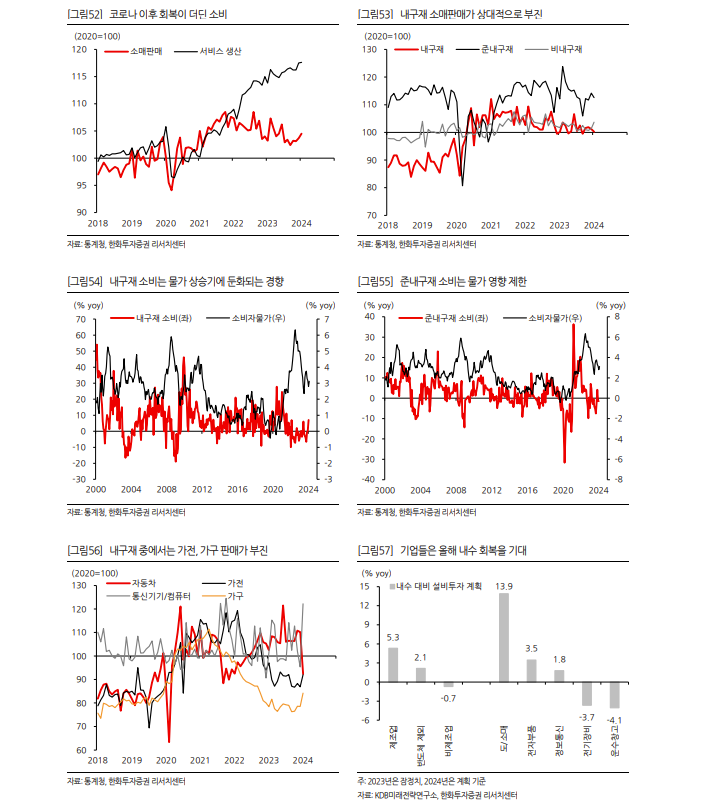

Now, many economists believe that the federal-funds rate could settle in the mid–3% range, or even as high as 4% over the longer term. Adjusted for inflation, that implies an anticipated real neutral rate of 1.5% to 2%—three or four times the level that officials were predicting a few years ago.

“That is a very different world from the world we left,” says Diane Swonk, chief economist with KPMG.

There is a catch. The neutral rate can’t be measured, and can be estimated only in hindsight. Yet gauging its level is paramount for Fed policy makers as they weigh whether and when to cut interest rates, and how best to minimize economic damage while cooling inflation further.

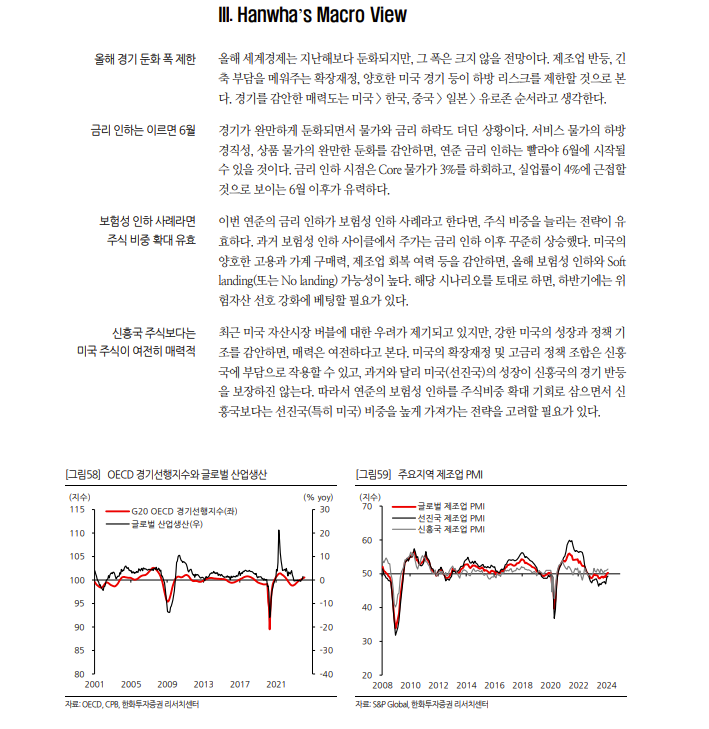

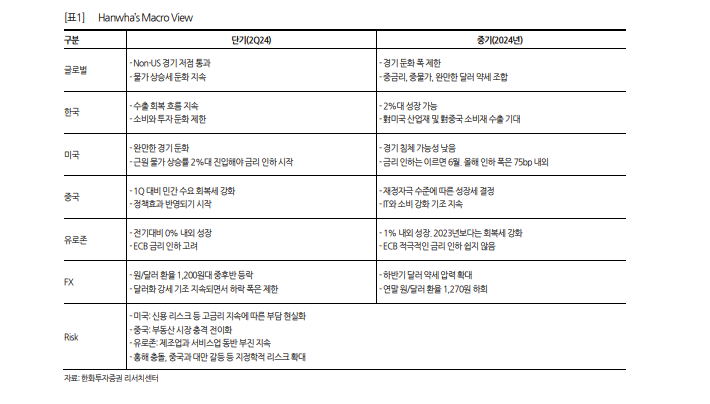

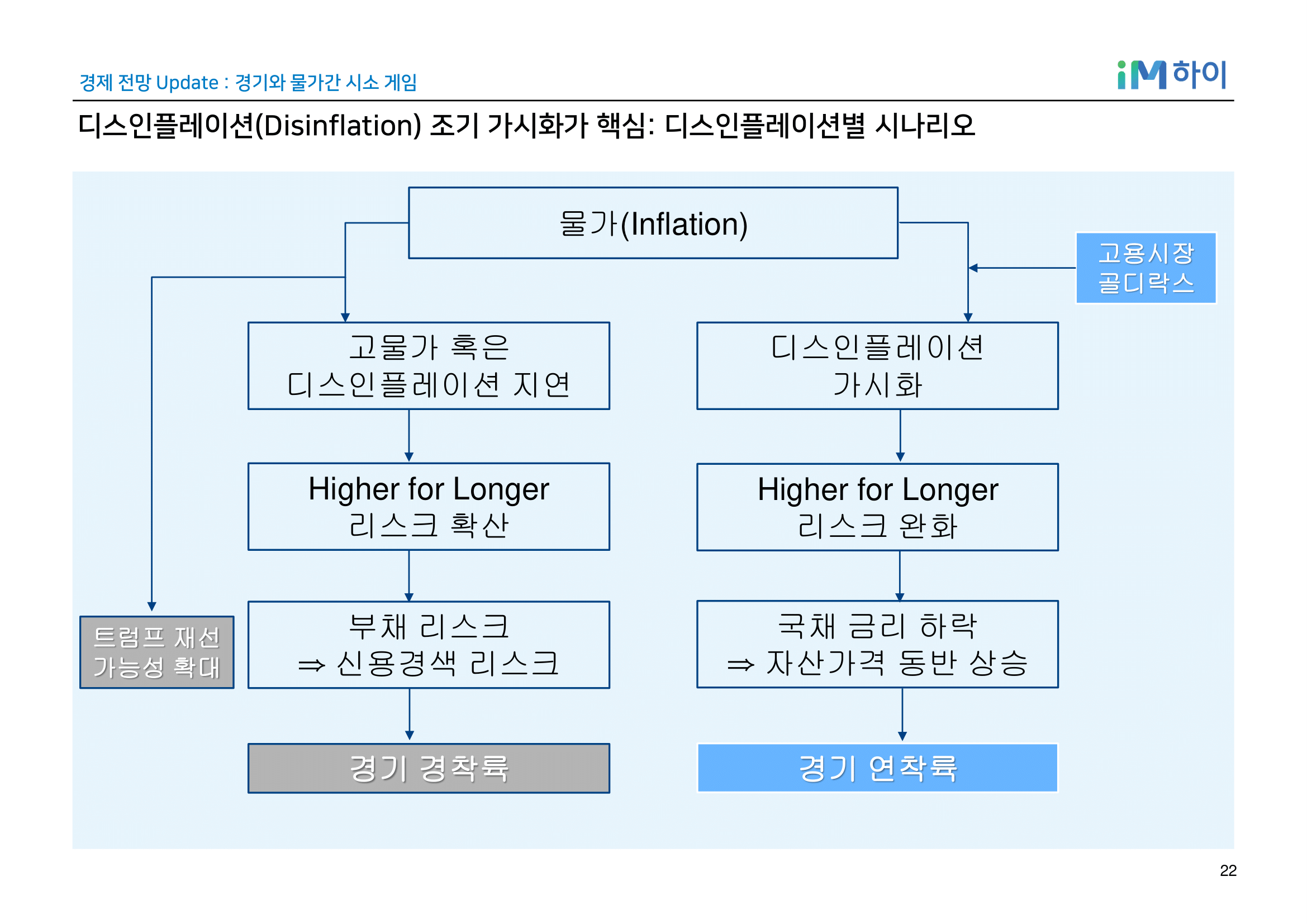

If officials assume that the neutral rate is higher than it really is, they risk overtightening monetary policy. If they assume it is lower, as some economists fear the Fed is doing, they risk tightening insufficiently, thereby allowing the economy to reflate within a matter of months. Taming resurgent inflation would require even more painful monetary tightening.

“Part of the reason why I think many of the projections, including those in the markets, for cutting rates overdo it a bit is because they presume that policy is more contractionary than it already is,” says former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers. “They assume too low a neutral rate.”

Expect the debate over “neutral” to dominate economic policy discussions in the coming months. But it will take on even greater importance thereafter, as economists and Fed officials attempt to map out what the economy might look like once price growth settles back to the Fed’s 2% annual target, and how it will compare with the pre-Covid era.

To be sure, a higher neutral rate isn’t a foregone conclusion. Opinions vary, and unexpected events, such as another financial crisis or pandemic, could force the Fed and other central banks to push rates much lower.

But for now, even Fed officials have begun to signal that they believe the neutral rate is rising. In the central bank’s quarterly projections released in March, only four officials wrote that they believed the neutral rate had climbed above 2.5%. By September, seven officials said the same. Officials will publish their latest projections on Dec. 13, at the close of the Federal Open Market Committee meeting.

The long-run implications of a higher neutral rate are substantial. Money would no longer be as cheap as it was for much of the 2010s. Debt would be more costly, and loans would be more difficult to secure. Start-up businesses would face heightened pressure to turn profits quickly, and fewer would get off the ground.

Advertisement - Scroll to Continue

But there would be benefits, too. Savers and retirees would profit from higher-yielding fixed-income investments. Higher rates would encourage more saving and more-efficient capital allocation. And central banks would have room to adjust rates lower in the event of an economic slowdown, which would make for a less volatile economy.

“This, in my mind, is the single best financial market development in the past 20 years,” says Joseph Davis, global chief economist at Vanguard. “And there’s nothing close.”

It wasn’t so long ago that economists and policy makers were focused on why wage and productivity growth were so sluggish, and whether inflation would ever climb back to the Fed’s annual 2% target growth level. Despite more than a decade of ultralow rates, core personal-consumption expenditures—the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge—topped 2% in only five months from 2010 to 2020.

The explanation that was growing in popularity before Covid hit was that the neutral rate must be lower than anyone had thought. Slowing productivity and an aging workforce appeared to be weighing down the economy in such a way that monetary policy would need to remain loose for price growth to return to target.

Ultralow inflation and ultralow interest rates were making for an unusual equilibrium. “It’s hard to get out of that cycle without a major shock,” says Kristin Forbes, an economics professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Then Covid arrived, upending the global economy. While the factors believed to be dragging down the neutral rate pre-Covid haven’t been eliminated, they have now been overshadowed by fresh changes that have left the economy more prone to global shocks and bouts of inflation.

Advertisement - Scroll to Continue

“We went through the proverbial looking glass, into a mirror image of the world we left,” says Swonk.

Among the most influential changes has been the ballooning of government deficits, and the propensity of many Western governments to spend freely on policy initiatives without ensuring a commensurate increase in tax revenue to offset the costs. In the U.S., debt held by the public ballooned as a share of overall GDP from 79.4% in 2019 to 99.8% in 2020, and it’s projected to increase sharply in the coming decade. Data from the International Monetary Fund show that a number of European countries, including Germany and the United Kingdom, have seen similarly steep rises in recent years.

This increased deficit spending is due partly to the post-financial-crisis embrace of quantitative easing by central banks, which gave governments a regular buyer for their debt, says Torsten Sløk, chief economist at Apollo Global Management.

The combination of reduced savings and increased spending will stimulate the economy, pushing up the neutral rate over time. And a number of new trends suggest that generous federal spending is poised to continue. Consider governments’ embrace of climate-change mitigation: The continuing green transition will require expensive investments to find alternative sources of energy, while the increased frequency of natural disasters and other weather events will require costly recovery efforts.

Aging populations, too, require elevated levels of government spending on healthcare and entitlement programs, which will be major contributors to the forecast rise in the U.S. deficit in coming decades, barring political changes. Likewise, rising geopolitical tension has necessitated an increase in military spending in high-income nations. The war in Ukraine pushed total global military expenditure up 3.7% in 2022, and European spending saw its largest year-over-year jump in at least 30 years, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Future totals could edge higher still: In the U.S., the proposed Department of Defense budget for fiscal-year 2024 came in 5% above the level that had been anticipated a year earlier, and the Congressional Budget Office forecasts that the agency’s overall costs will rise10% from 2028 to 2038.

Advertisement - Scroll to Continue

Heightened global tension is one result of a trend toward global fragmentation, which has led to a slowdown in worldwide trade and a renewed focus on building supply chains closer to home to minimize risk. Both shifts are likely to stoke inflation and weigh on growth. In a similar vein, an industrial-policy push for more domestic production of technology such as semiconductors has led to an increase in the use of government subsidies to incentivize investment in higher-wage nations.

In all, annual public expenditure in the U.S. could increase beginning next year by a level equivalent to 2% of gross domestic product, says Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics. Other Group of Seven nations and China, he adds, are behind the U.S. but on a similar track.

“This is substantial,” Posen says. “And there is very little prospect in the near term for raising taxes.”

There is no telling yet whether any of these shifts will become permanent. But their impact has already been greater and more persistent than initially expected, a point that European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde made in a speech at the Fed’s Jackson Hole economic policy symposium in August.

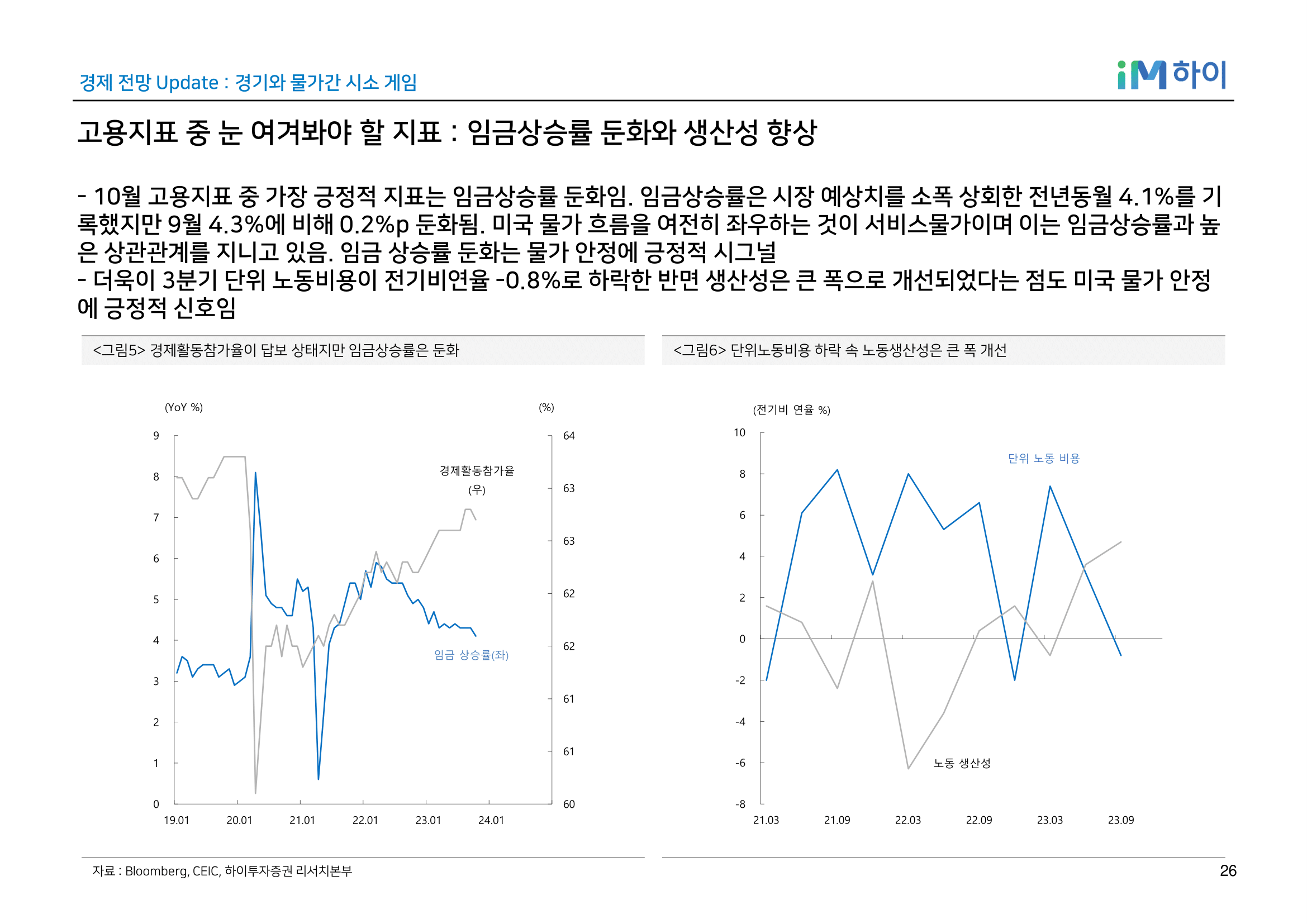

That could have significant implications for the Fed’s inflation fight, where progress in reducing core inflation from a current annual rate of 3.5% down to 2% could prove slow. More important, it could also affect where price growth and the neutral rate settle in the future.

Says Summers: “2% is looking more and more like a floor on inflation, rather than an average inflation rate over time.”

Even assuming the neutral rate has risen, there is disagreement about what this will mean for the economy and whether it will help or harm business owners, consumers, and investors.

One concern is that higher rates could throw sand in the gears of the housing market by exacerbating affordability problems. In the U.S. especially, where many homeowners locked in 30-year mortgages in recent years at rates below 4%, there is an incentive to stay put rather than move, given how much more expensive the next loan would be. As a result, prospective home buyers are facing not only higher mortgage rates but also less housing supply, since fewer existing homes are coming on the market than in the past.

Advertisement - Scroll to Continue

One ripple effect could be a less efficient labor market, says MIT’s Forbes. Mobility has long been a hallmark of the U.S. economy, helping to support wage growth by allowing workers to move to take a more lucrative position.

“If you’re constrained because you don’t want to sell your house,” Forbes says, that can “take away some of the bargaining power of workers.”

The shift to a higher-rate regime over the long term will also tax millions of companies launched in the past 15 years, which have never known anything other than the easy-money policies that have prevailed since early 2009. That could lead to at least a brief increase in bankruptcy filings as the corporate sector adjusts to paying more to borrow money.

It could become more difficult for firms to get off the ground, too. For much of the past decade, entrepreneurs could borrow capital at little cost, allowing them to keep their doors open for years without turning a profit. “Now, you need to have a business that actually makes money, and makes money sooner, because the discount rate goes up,” Sløk says.

When debt costs more in a higher-rate world, there is less money available for otherwise fruitful investment, a shift that will be felt particularly in the public sector. U.S. interest costs nearly doubled from 2020 to 2023 and are the fastest-growing area of government spending, says the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. The U.S. is on track to spend more than $13 trillion on interest costs over the next decade, the committee projects.

Given that growth, the average citizen will get less value from the government, Posen says.

Advertisement - Scroll to Continue

“To make it sound very bloodless,” he continues, “there is a robust empirical relationship across countries over time that if you have higher government interest payments as a share of GDP crowding out private-sector and public-sector investment, you have low innovation, a low rate of productivity growth, a low rate of growth overall.”

That said, the transition away from easy money has benefits, too, even if the positives are more often overlooked.

Although a higher cost of capital means that loans might be harder to come by, the best ideas will still find funding. And better capital allocation means funding will go to innovations, technologies, or projects that are best poised to take off. That could lead to better economic results, says James Bullard, the former president of the St. Louis Fed.

“I love innovation as much as the next person, but it shouldn’t just be willy-nilly,” says Bullard, now the dean of the business school at Purdue University. “You may have better discipline if you have somewhat higher real rates.”

For investors, the benefits can be even more tangible. Savers will be rewarded as cash compounds, allowing for higher returns. That is particularly beneficial to older Americans, including many retirees, who tend toward more conservative fixed-income investments.

“You’re seeing a tidal wave of change in how people think about [getting] income into portfolios,” says Rick Rieder, chief investment officer of global fixed income at BlackRock. “You can now build a portfolio to get 6%, 6.5%, 7% yield using quality fixed-income assets.”

Even those who regard higher rates as a plus for both the economy and investors recognize that there will probably have to be a painful transition period before we settle into the next equilibrium. While the economy has handled the jump from near-zero interest rates to the current level remarkably well, due in part to sustained fiscal spending, signs of a slowdown have emerged recently. Those are likely to become more noticeable in the coming months as the restrictive regime takes hold more fully and so-called zombie firms propped up by stimulus spending and low rates start to collapse.

Then, the benefits will come.

Vanguard’s Davis pictures a bell curve when thinking about growth under various interest-rate levels. Exceedingly high rates such as those seen during former Fed Chair Paul Volcker’s era in the 1980s stifle growth. But near-zero rates can promote a sluggish environment, too, he says. While they might stimulate asset prices in the short term, long-term returns fall because there is no base rate to compound.

Settling somewhere in the middle brings the most benefit, notwithstanding any interim pain. “There is a transition here,” he says. “But I would take that transition any day.”

Write to Megan Cassella at megan.cassella@dowjones.com